Why I'm finally writing what every South Asian son thinks but never sends

Because some things are easier to write in a newsletter than say at the dinner table

I have been on the road for a while now, long enough that the days have begun to fold into one another, long enough that I can’t differentiate between what feels like a Saturday or a Wednesday, and today, as I write this, I find myself having slipped into another four-week stretch of trains and rented cars and borrowed beds. But even I have to admit that what I’m doing these few weeks is less book research and more a holiday. It’s a breather — from the writing, the research, or maybe just from the relentless need to justify every moment of this sabbatical. The guilt sits close to the surface, reminding me that I haven’t written as much as I told myself I would by this point; but this trip was fixed before any of that, before the deadlines became concrete, before the sabbatical even felt real. It was planned, after all, with my closest friends who decided they were coming to India even before I had booked my flights home.

Two of them are here already, and two more land this weekend, and suddenly my days are shaped by reunions and the familiar chatter echoing in unfamiliar places. And all of this has made me think about gratitude in a way I have not allowed myself to in a while; about how none of us ever do any of this alone. About how it is impossible to build a life like this, a life spent wandering and writing and trying to understand a country as vast and complicated as India, without a support system that not only cheers from the sidelines but also gets on a flight and shows up, simply because they want to experience your life from the inside. I am lucky to have that. I know I am.

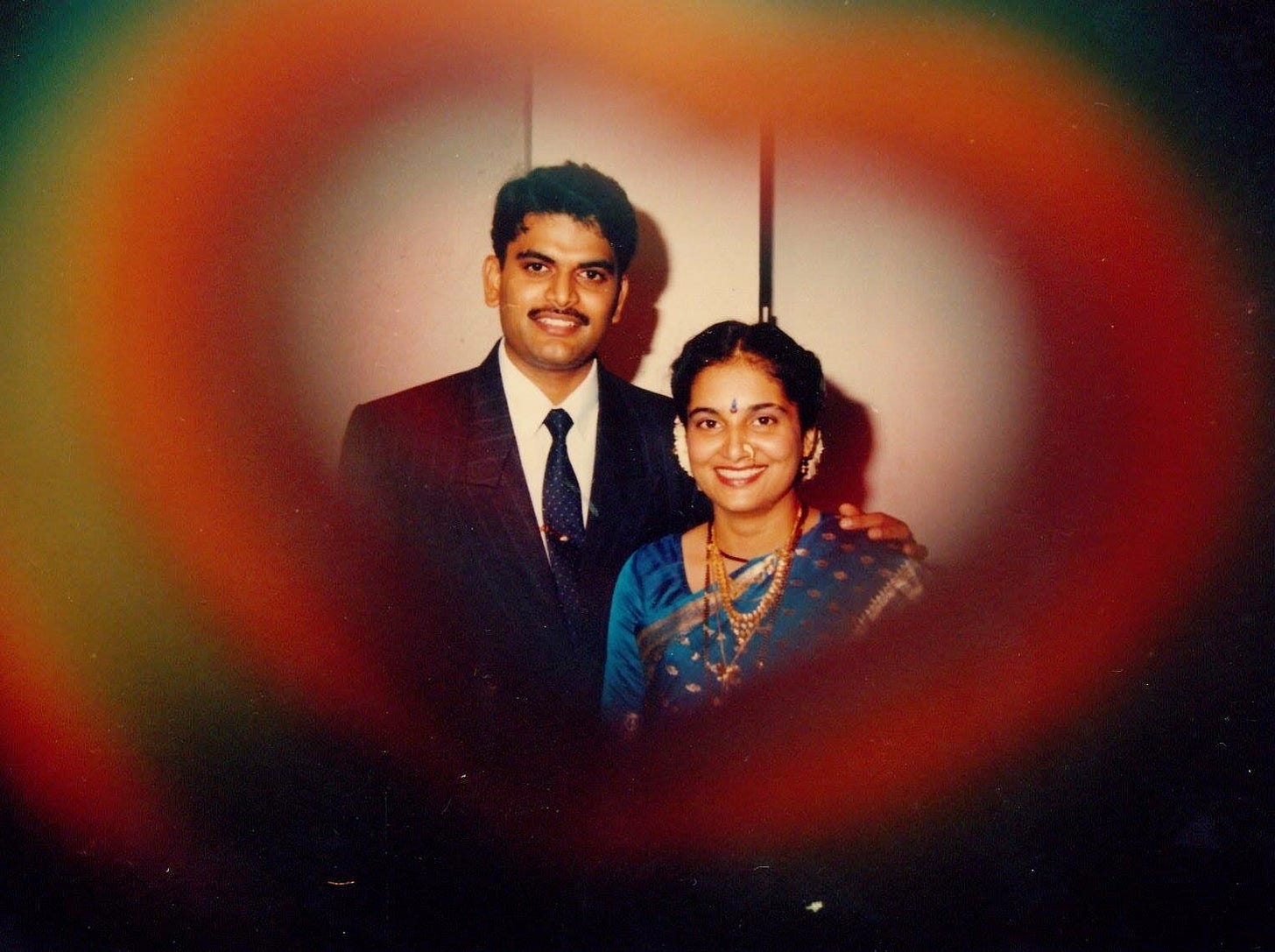

But there are two other people who keep coming to mind even more often in these weeks. Perhaps because tomorrow happens to be their anniversary, and maybe because this move back to India has also been the first time I have ever lived with my parents as an adult. I left home at eighteen and built a life in other cities, and coming back after more than a decade has been equal parts grounding and disorienting. But underneath all of it runs one steady feeling: a deep, old gratitude that I’ve been excavating.

Part of the hesitation comes from where I come from. South Asian families do not hand out emotional vocabulary the way they hand out food. Affection lives in the weight of a tiffin packed too full, in the way the light is left on and a meal is saved for you when you return late, in the silent sacrifices that no one names because naming them would make them too sharp, too real. And for South Asian men, especially, the language of softness is restricted to two spaces: romance and banter among friends. Anything outside that is treated with suspicion, even ridicule. We grew up on films where parents existed as caricatures: either jumping around making inside jokes like overgrown teenagers, or stone-faced antagonists who’d eventually melt in the face of love (think DDLJ). Never as people with internal lives that shifted and deepened over decades. Romance was allowed centre stage; filial love was something you were meant to intuit, not articulate.

We learned to read love in the negative spaces — in what wasn’t said, what wasn’t asked for, what wasn’t expected in return. My father’s pride lived in introducing me to his colleagues and letting my mother and I use his card when we went out shopping; my mother’s care in the way she still asks if I’ve eaten, even when I’m thirty-one and supposedly capable of feeding myself. And I learned to speak this same language back: taking them along on my travels when I could, messaging Aai on Valentine’s Day because she finds it amusing, picking up dinner tabs before Baba can reach for his wallet, sending money home even when he insists he doesn’t need it — small rebellions against their self-sufficiency to show them I love them. But this linguistic poverty around affection creates its own kind of inheritance: generations of children who know they are loved but have never heard it said plainly, who then struggle to say it to their own children, and so the cycle continues.

But I do not think that silence serves us — or at least me — anymore. There is a different kind of adulthood that arrives when you finally see your parents as people and not just the architecture of your childhood — people who became parents younger than you are now, who were allowed to change their minds and grow into different versions of themselves decade by decade, even if you were too busy becoming yourself to notice. And once that happens, the old script of unspoken gratitude feels insufficient. It feels almost dishonest.

So I want to say this today. Thank you, Aai and Baba, for being the ground that held steady even when everything else shifted. Thank you for struggling in ways I did not witness so that I could grow up believing that the world was open to me. Thank you for making sure my education was paid for, even when that meant tightening your own lives. Thank you for supporting friends and relatives when you had your own battles. Thank you for teaching me the value of pursuing my own happiness instead of solely running behind money. Thank you for giving me the privilege of curiosity, something I now realise is one of the greatest gifts a child can receive.

And maybe I’m not alone in wanting to say this. So for all of us who struggle with these words, here’s what we want to say: Thank you for becoming different people than your own parents so we could become ourselves. Thank you for swallowing your own dreams so quietly we never knew they existed until we were old enough to feel guilty about it. Thank you for translating love into action so consistently that we mistook it for the natural order of things. Thank you for never asking us to thank you, which is probably why it’s taken us this long to try.

When I told you I was thinking of leaving my job to write a book, your reactions were almost comically opposite and yet perfectly complementary. Aai, with her bright, almost disarming optimism — a kind of beautiful naivety that refuses to be cynical even when the world has offered every reason to be — simply said, “Why wouldn’t you do this? This is your dream. You’ve always been creative. Take the time. Write the book.” She believed in the version of me I was still afraid to fully acknowledge.

Baba, meanwhile, listened to every practical anxiety I had over long calls. Anxieties like “what would this mean for my career?” “Could I really pick up consulting again if I needed to?” “Would I manage the finances of a sabbatical year?” He was the one who validated the underlying fear that lives in most men my age, the fear of shedding a corporate identity that has become a shield, a shorthand for stability and success. He didn’t dismiss those fears, but helped me map them, name them, understand them. And by the end of those conversations, I realised that I wasn’t reckless for wanting this life. I was prepared for it.

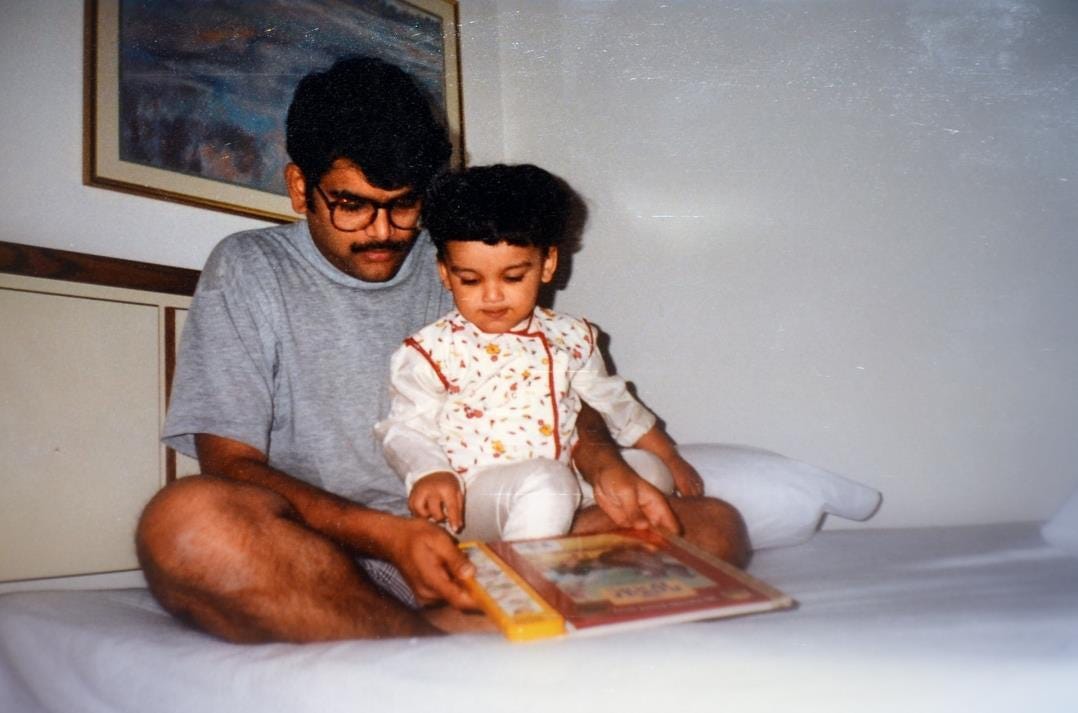

If I can take risks now, it is because of them. If I feel the confidence to step off well-trodden paths, it is because for decades they held the map while I learned how to walk without it (although let’s be honest, I still Google Maps my way around India). After a decade spent continents apart, this unexpected time under the same roof has become its own kind of blessing — not one any of us wants indefinitely, but one I’m grateful to experience in this moment.

Living with them again has taught me just how hard it has been for their generation. We talk about generational trauma, about patterns passed down, but what we don’t talk about enough is that they were the sandwiched generation: they had to obey their parents unquestioningly and then, with barely a pause, had to adapt to the demands and dreams of their children. They became translators between two worlds that barely spoke the same language. They had to somehow honour parents who believed suffering built character while raising children who believed happiness was a legitimate life goal. They straddled arranged marriages and love marriages, joint families and dating apps, duty and desire. Every family gathering became a negotiation, every life choice a careful calculation between what would disappoint their parents least and what would fulfill their children most.

That kind of generational whiplash is rarely acknowledged, but it reshaped families like mine. It softened something. It created room for kids like me to claim the independence we felt entitled to. But it must have been destabilising — creating space for conversations their own parents would never have entertained, building a framework where none existed before.

So I am grateful to be a beneficiary of that shift. I think, sometimes, that I’ve spent so long trying to build a life of independence that I forgot independence is only possible when someone gave you a stable foundation first.

Perhaps this is what travel really teaches us — not just about new places but about the distances we’ve already traveled from home, both literal and metaphorical. Every guesthouse and train compartment becomes a mirror reflecting back the stability we take for granted. Every solo meal reminds us of tables we once rushed to leave and the ones we were excited to join. And maybe that’s why my friends flying across oceans to be here matters so much: they’re choosing to collapse that distance, to say that some connections are worth the price of a plane ticket and jet lag.

I wrote this piece and wasn’t going to hit send. Part of me thought: of course my parents know I love them, do I need to send a mass email to my audience — many of whom want to read about actual travel — so that they read it too? But this is part of the journey, for only this journey could have led me to feel this way. It’s only on trips like this that you realize what you forget in corporate boardrooms: that freedom is not the opposite of belonging. That you need a tribe even when you’re independent. That gratitude is not childish. And that love, especially the non-romantic kind, is allowed to take up space on the page.

Because it’s not just the crossing of borders that makes a journey. Sometimes we have to cross the distances within our own families. And that, I’m learning, is its own kind of travel writing.

Love this Nishad, very glad you shared it. Enjoy having your amazing friends with you ❤️

This is so well written!