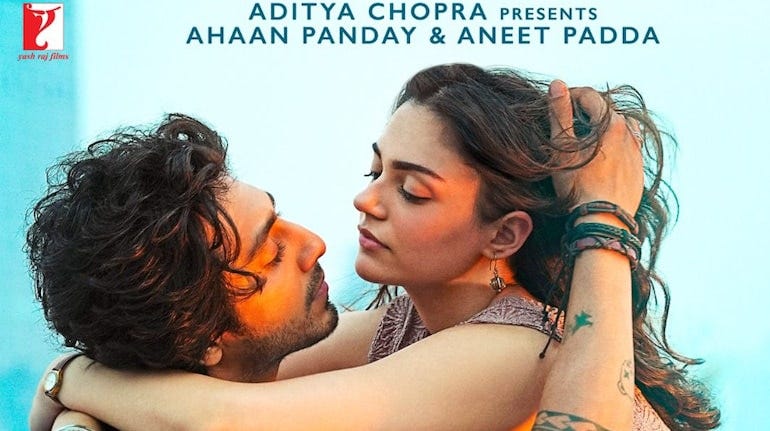

He’s not deep, he’s just damaged

REVIEW: What Saiyaara gets wrong about masculinity, rage, and the fantasy of fixing broken men

There’s a certain kind of man we’ve seen over and over again in pop culture, across languages and industries. He’s angry, volatile, emotionally unavailable, often violent. He sulks, drinks, lashes out — and somewhere beneath the mess, we’re told, there’s something beautiful; that he’s just one heartbreak away from redemption, and so, that makes him wort…