An Empire built on sand

REVIEW: Scott Anderson’s unsparing portrait of the Shah of Iran, Cold War America, and a doomed partnership that mistook power for permanence

Note from the road: I’m travelling this week — when this review goes live, I’ll just have crossed the Atlantic into Nova Scotia. But I didn’t want to miss the moment: King of Kings is out tomorrow, and it’s a searing, timely book that deserves a deeper look. So here’s my take.

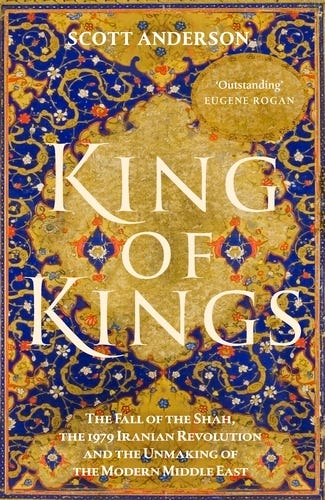

King of Kings by Scott Anderson

Hutchinson Heinemann, August 2025

I still rememb…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Infinity Inklings to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.